“She was impossible. Every suggestion you made, she fought; you fought with her all day long,” said Mitchell Leisen about directing Veronica Lake in I Wanted Wings, her first film as a star. “She was a pain in the ass,” said Randy Grinter, the son of Brad Grinter, who directed her 25 years later in her last movie, Flesh Feast.

Ah, yes, Flesh Feast. A movie about a mad scientist, flesh-eating maggots, and Adolf Hitler. It’s nowhere near as good as it sounds. We’ll get around to it; there’s really no hurry. Let’s talk about Veronica Lake first—the difficulties that made her so “impossible,” and the legacy of performances those difficulties have obscured.

She’s remembered today for two things. Her silky and suggestive teamings with Alan Ladd in a series of prototypical 40s films noir. And her hair, hanging down in luxuriant blonde waves and half-obscuring her right eye. In an era when movies wore a sexual straightjacket, this sultry “peekaboo” hairstyle caused a national sensation. Such is the enduring power of her star image that Kim Basinger won an Oscar for attempting to evoke it a half-century later in the neo-noir L.A. Confidential. At one key point in that film, Russell Crowe’s detective drops his tough-guy act for a second and tells her “You look better than Veronica Lake.”

Nice line. But really—not even close.

Veronica Lake was gorgeous. Not just the hair, which was indeed spectacular, but also the high cheekbones, the petulant lower lip, the wary narrowed cat-like eyes that could widen suddenly and knock you out. Okay, so Hollywood is lousy with beautiful women and always has been. Lake had more than beauty, she had the mystery of a real movie star—an unreadable something. An amused, distant quality, a withholding that made you lean closer in. An unstable mixture of vulnerability and toughness, empathy and contempt. Even her beauty seemed on the edge of disappearing in a cloud of childlike petulance. Then that would pass, like a child’s bad mood. Warm-cold-warm-cold… like somebody idly flipping a light switch on-off.

This quality reads wonderfully on screen. Off it, not so much. Few liked her; many loathed her. Her life story was an unending series of antagonisms, frustrations, poor decisions, tragedies, scandals and sordid headlines—until it did end, not too long after Flesh Feast. She herself got little respect, not just as an actress but as a human being. She was the original Lindsay Lohan: trainwreck first, performer second. A paranoid schizophrenic, according to her mother. A drug addict, according to her second husband. A bitch, according to many of her co-workers. And a raging drunk, by unanimous consent.

“I was never psychologically meant to be a picture star. I never took it seriously,” she once said. “And I hated being something I wasn’t.” What she was, fundamentally, was an outsider. Her best roles and most memorable performances all tapped into this quality. She seems most fully herself when she’s bending or subverting her era’s ideas of what a good girl should do. When she tucks her hair under a cap and hops a freight train in Sullivan’s Travels, when she drops out of government work into a noir underworld with Alan Ladd’s haunted hit man in This Gun for Hire, or when she travels across a garden in the form of a puff of smoke in I Married a Witch. “I’m a lot older than you think,” she tells Fredric March in that film, but in fact she’s a lot younger than you think: she was only 19 when Leisen’s movie made her a star overnight.

Too much too soon, maybe. After winning a few beauty contests as a teenager in Miami, she was pushed into show business by her mother Constance, who moved her and her ailing stepfather across the country to get her into the movies. In later years, Constance was the source for the claim that she was diagnosed as a schizophrenic, but who knows? When somebody has a biography as fucked up as Veronica Lake’s, it can be hard to sort through the layers of finger-pointing, lurid rumor, repeated gossip, and outright lying (Lake herself was a frequent, flagrant liar). Let’s just say that acting lessons seem a strange therapy for schizophrenia. Also that it’s a bit unusual for a mother to give her daughter the same name—Lake’s birth name was Constance Ockelman, and everyone called her Connie. And then they had a second name in common. “My mother and myself never got along too well and that was from early childhood,” she recalled in a 1969 interview. “My mother’s real first name, it happens to be Veronica. And of all the names they picked [for me], it had to be Veronica.”

“A typical victim of a stage-mother’s dream turned into nightmare. From a miserable childhood packed with broken promises, shoved into the pitfall-littered labyrinths of Hollywood,” recalled her second husband, director André de Toth, in his (also a bit untrustworthy) autobiography.

Whatever the truth, it was a brief leap from dramatic school in Hollywood to bit work in movies, to catching the eye of a producer who changed her name and gave her the plum role in I Wanted Wings, as a bad-girl cabaret singer. Leisen recalled that she couldn’t handle dialogue very well at this point and he had to give her very simple movements. In her first shot in the film, she’s seen singing (dubbed) in front of a band in a nightclub. She caresses her thigh as she’s hit by a spotlight that sets off her clinging, shimmering dress, her cheekbones, her glistening head of hair. Leisen seems entranced. It’s a wow moment, and his camera knows it; he moves it in and circles her slowly, erotically.

That shot made her an instant star. Billed seventh, she dominated the posters for the movie and the publicity. The hair got most of it, as the fan magazines shrieked about it and women across America crowded salons wanting the same style. Meanwhile back at Paramount, Lake had already managed to piss off the studio by leaving for Arizona without telling anyone in the middle of filming, after taking childish offense to Leisen’s persnickety personality. With hindsight, it seems her first willful rejection of stardom just as it was being handed to her on a plate… the first of many such gestures.

For the moment, though, there was no stopping her. I Wanted Wings was Paramount’s highest grossing picture of the year, largely due to her. And the studio’s most successful and high-profile director, Preston Sturges, wanted her for his next film, Sullivan’s Travels. Sturges, a good-natured extroverted egomaniac, knew just how to handle her. The atmosphere on the set of his films was like “a carnival,” one actor recalled. When Lake revealed halfway through shooting that she was pregnant (she had just gotten married, probably to escape from Constance), Sturges didn’t fire her but instead laughed his head off and promised to dress her in baggier clothes. If Leisen is to be trusted about her inability to handle dialogue, Sturges must have taught her well, because she handles pages of his rapid-fire banter, firing back and forth at Joel McCrea in long, unbroken takes. And it’s some of the best dialogue she or anybody else ever had.

Sullivan’s Travels centers on McCrea’s character, a fatuous movie director who wants to move from comedy to drama, but finds the real Depression-era America a far cry from his privileged, ivory-tower concept of it. Widely regarded as Sturges’ masterpiece, it’s certainly his most personal and probing film. Lake is rarely given credit for her contribution to it, but she’s the emotional center of this complicated movie about The Movies. Her character, called “The Girl” in a bit of meta inspiration by the filmmaker, is bitter and tough on the surface, but genuinely hurt by Sullivan’s selfish obtuseness. Paired with the 6′ 2″ McCrea, she seems even more tiny than she was (4′ 11″), and she’s vulnerable and brave as she pretends to be a boy and tiptoes her way through a land of lecherous, threatening bums. Physically, she and McCrea are a mismatch, but her edginess and his dissatisfied crotchetiness seem made for each other.

Sturges liked her and set up another comedy for her, I Married a Witch. He selected another fine director, the French transplant René Clair. An ideal choice for the film, as Clair was an expert in fantasy and offbeat humor. And for Lake, who spoke fluent French (the Ockelmans had lived in Montreal for a time) and responded to a director who believed in her talent more than she did. According to Clair, Paramount knew they had something special in Lake and didn’t want an ordinary role for her, and it was Sturges who suggested Thorne Smith’s sexy supernatural fantasy “The Passionate Witch.” She’s perfect in it—a wicked sprite motivated by hatred and revenge until she drinks a love potion, at which point she becomes “itchy with sexual frustration,” as Guy Maddin puts it in his loving notes to the Criterion blu-ray. (There was some sniping on film forum boards when Criterion added this movie to its roster of Great Cinema… a curse on those mortals!) The movie is full of subversive fun, and Lake’s funny, mischievous, completely charming performance is her best claim to immortality.

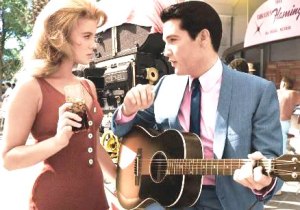

Between these two comedies came two more films that cemented her stardom and her legacy: This Gun for Hire and The Glass Key. They’re classified as film noir but they came early in that cycle, and so they’re compromised by the movie factory’s conventional efforts at morality and uplift. Just what audiences don’t want. But in both, the half that’s noir is still pretty terrific. In the first, Lake plays a nightclub singer engaged to a cop (Robert Preston), who is secretly recruited by the FBI to gather information on a ring of foreign spies. Contrived and absurd as this is, it leads to her involvement with Alan Ladd as Raven, an emotionally scarred hit man who’s been betrayed by the spies and is out for revenge even as he’s being hunted by the cops. Raven, the ice-cold killer who loves only stray cats, is the role that made Alan Ladd a star. And you can see why: he’s a stray cat himself who’s been kicked around by life and has to run and hide and make his own snarling way in the world. He kidnaps Lake, and while they’re on the run they begin to develop an understanding. Ladd and Lake were both too cool as performers to be able to convincingly act “falling in love,” but here their tentative reaching out to each other feels emotionally satisfying, and the fact that it’s unexpected and transgressive (she’s engaged to his pursuer and he’s more than capable of killing her) gives their scenes a glamorous, sexy tension.

Paramount recognized the value of this team—they just didn’t quite know what to do with them. (A shame they didn’t give them Double Indemnity, in which she especially might have had a triumph. The Phyllis of James M. Cain’s book is petite and childlike, and Lake might have made a less obviously villainous mantrap than Barbara Stanwyck. Heresy, I know… but there, I said it.) The Glass Key was the follow-up, and it’s not as good as This Gun for Hire. Dashiell Hammett’s plot machinations are always a chore to follow, and without colorful characters to be interested in, this movie is all machinations. We want Ladd and Lake, but we get too much of Brian Donlevy as the lead character, a crooked politician trying to get respectable, and she is wasted in the nothing role of the girl both men want. The real romance in The Glass Key is between Ladd and William Bendix, as a terrifying thug. Bendix keeps beating Ladd to a pulp, all the while calling him “sweetheart” and “baby” and insisting that Ladd likes it, which is intriguingly possible. There’s a faint streak of masochism running through Alan Ladd, who in his private life had a house full of paintings of male nudes—less a reflection of his sexuality, perhaps, than of his lusting after size. He was famously short (5′ 6″) and Lake was one of the few actresses with whom he didn’t need to stand on a box. He died, as she did, a lonely and pitiful alcohol-fueled death at 50.

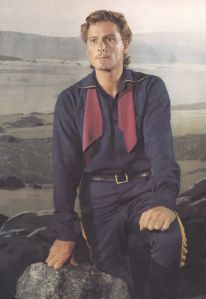

At this point, Lake had starred in four hits in a row, and the biggest hit of all came next. Unfortunately it led to her downfall. So Proudly We Hail was Paramount’s big patriotic wartime special of 1943, a tribute to the Red Cross nurses who served in Bataan and Corregidor. Claudette Colbert is the tediously sane and responsible head nurse, and Paulette Goddard is the wisecracking good-time girl. Lake, third-billed, plays a sullen, joyless bitch all the other nurses loathe. You can feel the executives at Paramount patting themselves on the back for all this typecasting. The war department had asked the studio to change the famous peekaboo hairstyle, because girls working in wartime factories were supposedly getting their Lake locks caught in machinery (she’s demonstrating the danger in the photo above). So for most of the movie, her hair is pinned up under her nurse’s cap. Going all dramatic, Lake has two big scenes in the film, the first when she breaks down and reveals that the Japanese killed her fiancé, the second when she sacrifices herself to save the other nurses. She appears in a doorway, hair suddenly loose for the sake of the fans, and slips a grenade into her blouse before walking toward the Japs with her hands up. These should be intense, impactful scenes, but they’re muffed by director Mark Sandrich, a ticktock craftsman who was utterly unable to convey emotion on the screen (historian John McElwee reports that one GI responded to Lake being blown to bits by yelling out “I know which part I want!”). Everyone seems to have decided Lake was nothing without her hairstyle, and Goddard got the Oscar nomination.

Paramount administered the coup de grace with her next movie: The Hour Before the Dawn. (It’s always the darkest, get it?) She plays a Nazi spy, complete with German accent. Skulking around Franchot Tone’s country estate, making shifty evil eyes with her hair up in braids, she’s borderline ridiculous and saves herself only by staying very still in most of her scenes. An actress with more experience and training, e.g. a less honest one, might have camped her way through this farrago. Lake looks utterly mortified. Her voice is soft and quiet, especially when she murmurs “heil Hitler” after a radio broadcast. I mean: of all the things to make an established, glamorous movie star say at the very height of World War II. In this and her other scenes, she looks like she’s physically restraining herself from running off the set. Can a single movie kill a career? This one did.

Meanwhile, her personal difficulties were only increasing. Miscarriage, divorce, squabbles with co-workers, and more and more partying. Her contract had four years to run, but the studio had already given up. They tossed her into three brain-dead musical comedies with chinless, sexless comic Eddie Bracken, who remembered “they called her ‘the bitch’ and she deserved the title.” But then, who wouldn’t be a bitch if they had to make three movies in a row with Eddie Bracken? Then they put her in a series of cutesy period pieces designed to show off co-star Joan Caulfield’s apple-pie charm, movies which neutralized every single thing that had ever been special about Veronica Lake. Implicit in them is a heavy corporate rebuke for the difficulties she’d caused and the enemies she had made. She was 25 years old, and her career was effectively over.

She had married de Toth around this time, and he directed her twice for other studios. Ramrod is a tricky, intermittently fascinating noir Western in which Lake plays the willful daughter of a rancher who uses her wiles to get all the men in the story to fight, betray and kill each other. De Toth called this character “a wicked, conniving lady, stronger than a man, with velvet balls,” but Lake really isn’t up to a Stanwyckish role like that. As an actress she was soft and insinuating; she nails the bitterness but can’t convey the strength. In Slattery’s Hurricane, she has an unattractive part as the girl the hero doesn’t want while he chases after another man’s wife. Her character turns to drugs, but the censors made sure this one interesting aspect of her part was carefully whitewashed. Instead, she just seems jittery, forlorn, and all too believably washed up. It was her last movie in Hollywood.

The drug addiction was an unkind touch; in his book, de Toth alludes several times to her “monkeys.” He doesn’t elaborate, but he does provide the most sympathetic portrait of any of her contemporaries. He describes two Connies co-existing in one person: “One hurt, timid, and scared. Not many—if any—were more insecure, shy and vulnerable. She was afraid and lonely and lived alone with her fear. Too proud to call for human help. The other loud, bitter, boisterous, got lost in ‘tinsel town, the shit capital of dreams,’ where she drowned herself in blind hatred.”

He goes on to say that “actually she, the real She, didn’t exist anymore. ‘That one was sold,’ she told me, at fifteen, as a down-payment for her mother’s dreams.” Around this time, her mother sued her for lack of financial support, as agreed when she’d become a star. The tabloids of the time had a field day. Constance won her suit, but later claimed that Connie sent her nothing but rubber checks. The marriage broke up in a flurry of even more ugly headlines as the couple declared bankruptcy and blamed each other. He got custody of their children. Now there really was nothing, except the one friend who had remained loyal: alcohol.

“She left,” de Toth wrote, “with the ethereal smile of a Kamikaze.”

Not just unemployable but practically radioactive on the West Coast, she headed East, where there was still some work to be had. On stage and in early blurry television, where if you squinted you could still see “Veronica Lake” sometimes. For Connie, there was only drinking, more bad relationships, professional embarrassments and mishaps. She got tangled in the wires onstage as Peter Pan (another outsider role, and her reputed favorite). Her stage career came to a halt after a dance partner fell on her and broke her ankle. Eventually she found work pasting felt flowers on hangars in a Manhattan factory, and then, more congenially, as a barmaid at the Martha Washington Hotel for women, where the room was free and the booze flowed. She worked for tips in obscurity under the name Connie de Toth, until a reporter from the New York Post stumbled on her and made a story of it. More unflattering headlines. People began sending her money, which she returned with prickly pride, all except a check for a thousand dollars from her one-time lover Marlon Brando (their paths had crossed in the early 50s), which she had framed.

She wrote an autobiography and revealed herself as still smart and tough, if a bit loose with the facts (“the most vicious thing I’ve ever read,” sniffed Mitchell Leisen). And around the same time, she moved to Hollywood. Only this time, it was Hollywood, Florida… just north of Miami. A mutual acquaintance introduced her to Brad Grinter, who was looking for financing for Flesh Feast. She invested in it and was listed as co-producer, and was involved creatively (see “she was a pain in the ass,” above). You can put this down to the shaky judgment of a woman who’d been an alcoholic for a quarter century, but it wasn’t a totally crazy move. A few years earlier, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford had made a fortune in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane, starting a vogue for horror films starring the decaying leading ladies of the 1940s. And in fact, she made a little profit on Flesh Feast, according to Randy Grinter. But that may have been because the film’s budget was only $100,000—a pittance, even in Florida in the sixties.

And it looks it. The sets are Ed Wood-cheap, the locations are drab. Grinter doesn’t seem to know where or how to place the camera. (She complained about this in her autobiography, written after the movie was shot but before it was released a couple of years later.) The people on the screen—you can’t call them “actors”—stumble at times over their business and the banal, dead-sounding lines in the barely functional script. It’s a horror movie without atmosphere or suspense, just a few icky close-ups of maggots. The lead role is a lady doctor who has spent time in a mental institution and who is now working on a rejuvenation formula (thus the flesh-eating maggots). The star in this role is supposed to be Veronica Lake, but really it’s Connie Ockelman—a petite, puffy-faced troll who looks 10 years older than her 47 years, and is unrecognizable as a former divinity of any sort. Her voice, once “a tiny mellifluent purr” (Guy Maddin) is now, thanks to years of smoking and trying to project on stage, a coarse rasp. Her exaggerated gestures and facial expressions show a drunk’s lack of control, and her grimace of a smile reveals a mouthful of blackened, rotting teeth. The ruination she has visited upon herself is the only real, the only true horror on the screen.

And then they bring on Hitler.

It’s the movie’s big reveal. Some shady South Americans have invaded the house and the laboratory, seeking to have the doctor rejuvenate their leader, The Commander, so he can “take over zee world!” In the final, unforgettable scene, the doctor straps him to a table in her lab, and begins to administer the treatment. She speaks of her mother, whose portrait is conveniently on the wall. “She vas a good Cherman voman?” The Commander inquires kindly. “A servant of zee Third Reich?” The doctor sneers at this and growls “oh yes—as a guinea pig!!” The Nazis experimented on her mother, it seems… now the doctor will experiment on him. She brings out a Tupperware bowl full of maggots and begins applying them to der Führer’s face. As he begins whimpering and screaming, she tosses more and more of them onto him, laughing maniacally, uproariously. “What’s the matter—don’t you like my maggots?!” she yells. And suddenly, this idiotic, pathetic scene begins to resonate. Oh, it’s revenge for mother, all right. It’s payback for the stardom she didn’t want that was thrust upon her, for being reduced to a hairstyle and laughed at, for the talent that never got used, for the frustration of years of mediocre work and tabloid headlines and public shame, for the even deeper private shame, for a confused young girl tossed into a machine that chewed her up and spat her out. It’s what Connie Ockelman thinks of show business, of fame, and herself. Heil Hitler!

She died a couple of years later, alone and destitute, of acute hepatitis and renal failure. An outsider to the last. Only one of her children, and none of her ex-husbands, attended her funeral. In fact, she wasn’t there herself—her ashes sat on a shelf at the funeral home for years, until a friend finally paid the $200 bill for the cremation.

But Veronica Lake had gone long before that. The last the world saw of that particular apparition was in The Blue Dahlia, one final Ladd-Lake film noir Paramount made at the height of her difficulties with them. A last chance, and a last hit for her. The original script by Raymond Chandler is spotty, but it has some nice ideas—none nicer than the scene where they meet. Ladd is a flier who has returned from the war to find his wife first unapologetically unfaithful, and then dead. As the chief suspect and object of a manhunt, he takes to the road. Lake is the mysterious blonde who picks him up one rainy night. She’s the ultimate Los Angeles girl, materializing out of nowhere on the highway, a blonde vision behind the wheel, an outsider angel. She takes him to a hotel, you read between the lines, and then they part. They speak in the low, hushed voices that were such a big part of their beautiful chemistry. It’s hard to say goodbye, he tells her. Why, she asks; you’ve never seen me before tonight. “Every guy’s seen you before, somewhere,” he tells her. “The trick is to find you.”

Special thanks to Randy Grinter for sharing his reminiscences on the making of Flesh Feast.

NOTE: This post was written for the annual “Late Show” blogathon over at Shadowplay, featuring some very smart film bloggers considering the final films of notable directors and performers, all hosted by the wonderful David Cairns. Check it out!

You must be logged in to post a comment.